The Harmonic Evolution of Blues Music

You’ll discover that blues harmony evolved from simple three-chord African American work songs in the Mississippi Delta into today’s sophisticated harmonic language, incorporating dominant seventh chords, microtonal blue notes, and the iconic 12-bar I-IV-V progression that’s influenced everything from jazz to rock. While traditional elements like call-and-response patterns remain intact, modern artists now blend electronic beats with classic structures, creating cross-cultural collaborations that expand blues globally through digital platforms, and there’s much more beneath this deceptively simple surface.

We are supported by our audience. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission, at no extra cost for you. Learn more.

Notable Insights

- Blues harmony originated from African American communities, blending African musical traditions with work songs and hymns.

- The standard 12-bar blues progression using I-IV-V dominant seventh chords became the foundational harmonic framework.

- Microtonal blue notes and pitch variations created emotional expressiveness beyond conventional Western harmonic structures.

- Jazz influences introduced chord substitutions and chromatic passing chords, expanding traditional blues harmony.

- Modern blues incorporates electronic elements and global influences while maintaining core harmonic principles.

Roots and Cultural Origins of Blues Harmony

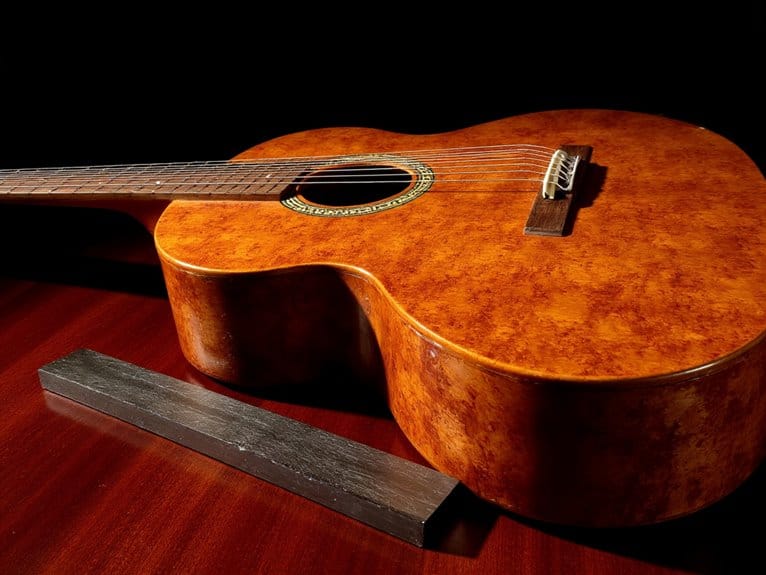

When you trace the harmonic DNA of blues music back to its origins, you’ll discover it emerged from the fertile cultural ground of late 19th-century African American communities, particularly in the Mississippi Delta where freed slaves channeled their post-Civil War experiences into a revolutionary musical language.

African influences shaped this harmonic foundation through syncopated rhythms, call-and-response patterns, and blue notes that bent traditional Western tonality into something entirely new.

The historical context of Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras provided the emotional framework, while spiritual origins from work songs, field hollers, and Christian hymns contributed structural elements.

This cultural resilience transformed pain into artistic expression, creating harmonies that spoke directly to the African American experience with remarkable authenticity and power. European harmonic concepts merged with these African traditions to create the foundational chord progressions that would define blues music for generations to come.

The early blues found its social context within juke joints, intimate venues where African Americans gathered to share music and community during the challenging post-slavery era.

Distinctive Structural Elements and Chord Progressions

From these deeply rooted cultural foundations emerged the blues’ most defining characteristic: a deceptively simple yet infinitely expressive harmonic framework that I’ve come to appreciate as one of music’s most elegant structural innovations.

You’ll find that distinctive progressions built around the foundational 12-bar structure create remarkable musical flexibility through their strategic use of dominant chords.

The essential elements that define blues harmony include:

- Standard 12-bar framework using tonic (I), subdominant (IV), and dominant (V) chord relationships

- Dominant seventh chords (I7, IV7, V7) providing characteristic “twangy” blues tonality

- Harmonic ambiguity through omitted thirds and major-minor scale mixing

- Jazz-influenced variations incorporating substitutions and chromatic passing chords

- Structural features like AAB patterns, walking bass lines, and turnarounds

This harmonic blueprint served as the foundational framework for improvisation and songwriting across multiple generations of musicians, allowing for creative expression while maintaining the blues’ essential character. Many blues forms evolved beyond the standard twelve-bar structure to include eight-bar blues and sixteen-bar variations that provided musicians with additional creative possibilities.

Microtonal Characteristics and Theoretical Frameworks

Beyond these foundational harmonic structures lies perhaps the blues’ most fascinating and theoretically complex aspect: the microtonal characteristics that I’ve discovered transform simple chord progressions into deeply expressive musical statements through subtle pitch variations that exist between the standard twelve-tone equal temperament system.

When you examine Robert Johnson’s recordings, you’ll notice these “blue notes” aren’t simply flat thirds or sevenths, but rather neutral tones that create emotional expression through precise microtonal singing techniques. These pitches, often explained through just intonation ratios like the 6/5 interval for lowered thirds, connect blues to African musical traditions while blending cultural tuning systems.

Each performer’s unique microtonal approach creates that characteristic “tragic” affect, making blues a living example of cross-cultural musical amalgamation. The microtonal interest in blues can be traced directly to West African slaves who sang these in-between notes as documented expressions of their musical heritage. The precise pitch of these blue notes varies by individual musician and their emotional state during performance, making each interpretation uniquely personal.

Modern Adaptations and Global Impact

While those microtonal nuances I’ve described represent the blues’ deep historical roots, today’s artists have transformed this foundation into something remarkably expansive, weaving traditional Mississippi Delta elements with electronic beats, synthesizers, and global influences that would’ve been unimaginable to Robert Johnson.

This blues innovation has created fascinating cross-cultural musical landscapes through strategic collaborations, digital integration, and genre-blending approaches that maintain emotional authenticity while expanding sonic possibilities:

- Artists like Gary Clark Jr. merge classic riffs with contemporary rock elements, bridging generational gaps.

- Electronic production techniques using drum machines and loop pedals enhance live performance dynamics.

- Jazz improvisation and syncopated rhythms create urban-influenced hybrid subgenres.

- International musicians contribute regional instruments and cultural rhythms to traditional blues frameworks.

- Digital platforms facilitate global collaborations, exposing blues to worldwide audiences beyond American origins.

These global collaborations demonstrate how traditional harmonic structures adapt brilliantly to contemporary musical contexts. Artists like Connor Selby exemplify this evolution with releases that showcase deeply introspective lyrics while maintaining blues authenticity. The resurgence of interest in both formats is evident as vinyl record sales have reached impressive heights, showing how audiences embrace both innovative and classic approaches to blues music.

On a final note

You’ve witnessed how blues harmony evolved from African polyrhythmic traditions through twelve-bar progressions to microtonal blue notes that bend conventional Western theory. I’ve traced this journey from Delta origins to global fusion, showing you how dominant sevenths, diminished chords, and quarter-tone inflections created music’s most influential harmonic language. You’re now equipped to recognize these elements, whether you’re analyzing classic Muddy Waters recordings or contemporary indie rock that borrows blues DNA.